Toni Cade Bambara: Writer, Activist, Culture Worker

By Elodie Barnes | On October 12, 2025 | Updated October 13, 2025 | Comments (0)

Toni Cade Bambara (born Miltona Mirkin Cade, March 25, 1939 – December 9, 1995) was a writer, civil rights activist, teacher, and documentary film-maker.

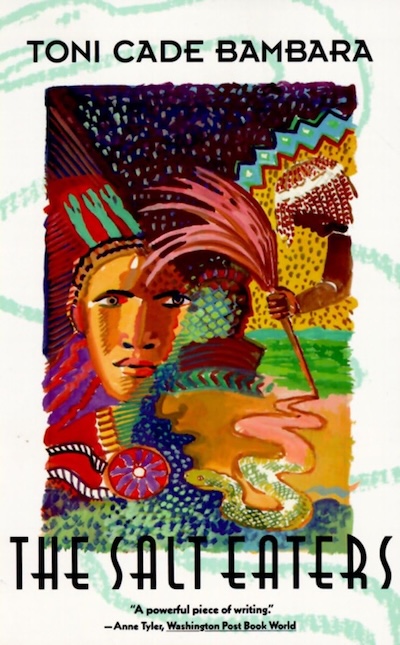

Well known for her 1980 novel The Salt Eaters, she was also hugely influential in the Black liberation and feminist movements. Her writing was inspired by the Black communities in which she lived and worked. She was concerned with injustice and oppression in general and of Black people in particular.

“A large repertoire of stories”: Growing up in Harlem

Toni was born in Harlem, New York. She spent her childhood and adolescence with her parents, Helen Brent Henderson Cade and Walter Cade, and her older brother, Walter Cade III, in Harlem and in Jersey City.

She changed her name from Miltona to Toni at the age of six. Much later, in 1970, she added the name “Bambara” – a national language of Mali and the name of a West African ethnic group, after seeing it inscribed in one of her great-grandmother’s sketchbooks.

Her mother encouraged her daughter in reading and the arts, and was a community activist in some of the organizations that sprung up in Harlem. That meant that music, theatre, writing, and activism were all bound up for Toni from an early age.

She was an average student in most subjects. Her fifth grade teacher at The Modern School, a private Black-run all-girls’ school in Harlem, reported that she was “not outstanding from either a scholastic or social point of view.” She did excel in creative writing, and she spent a lot of time at the New York Public Library. Later, she would cite poets Gwendolyn Brooks and Langston Hughes as major influences on her writing and her activism.

Graduate life

Although Toni considered studying medicine, she graduated from Queens College in 1959 with a BA in Theatre Arts and English Literature. She was active in various forms of the arts in college, and was a member of its dance club, and in theatre groups where she took on backstage roles such as stage manager and costume designer. She also won the university’s John Golden Award for Fiction.

In 1961 Toni traveled to Europe. There, she studied Comedia dell’Arte at the University of Florence, and mime at L’Ecole de Mime Etienne Decroux in Paris. On her return to America, she completed an MA in Modern American Fiction from City University of New York.

Toni worked in social services to support herself, as a social worker at the Harlem Welfare Center and an occupational therapist in the psychiatric ward of the Metropolitan Hospital.

After completing her graduate studies in 1965, she was offered the chance to help with the development of City University’s SEEK (Search for Education, Elevation, Knowledge) program for economically disadvantaged students. She continued to teach there until 1969, when she was appointed assistant Professor of English at Livingston College (part of Rutgers University).

In 1970, she had a daughter, Karma Bene Bambara Smith, with her partner Gene Lewis.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

Writing as transformation

Toni’s activism work and her writing grew side by side: “Writing,” she said, “is one of the ways I participate in transformation.”

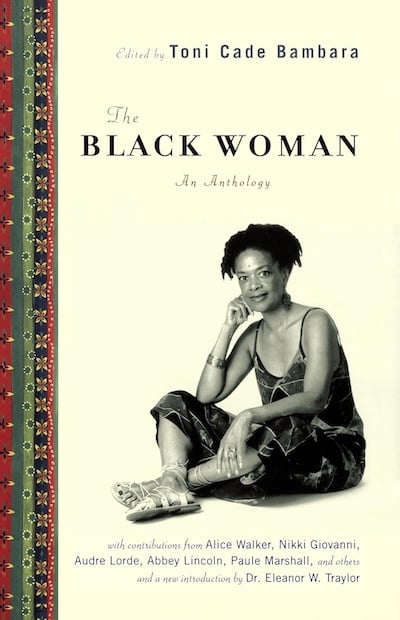

In 1970, she edited and published one of the first major anthologies of Black women’s writing, The Black Woman. It included well-known and celebrated writers like Audre Lorde, as well as some of her undergraduate students and other unknown writers, all of whom were underrepresented in the male-dominated civil rights movement and in the white-dominated feminism movement.

This was followed in 1971 by Tales and Stories for Black Folks, which celebrated what she called “our great kitchen tradition.” Toni was one of a group of Black women fiction writers in the 1970s, including Alice Walker and Toni Morrison. The latter would become her editor and a lifelong friend.

Her debut collection of short stories, Gorilla, My Love, was published in 1972, and her first novel The Salt Eaters (1980) won the American Book Award and the Langston Hughes Society Award. Another collection of short stories, The Sea Birds Are Still Alive, was published in 1977, and another novel Raymond’s Run in 1990.

Toni Cade Bambara’s stories were set in either the rural South or the urban North, and use dialect to portray the lives of African Americans (often activists) and their communities. She consciously used language to try and explore the Black experience:

“…there have been a lot of things going on in the Black experience for which there are no terms, certainly not in English, at this moment. There are a lot of aspect of consciousness for which there is no vocabulary, no structure in the English language which would allow people to validate that experience through language. I’m trying to find a way to do that.”

Toni Morrison said of her writing, “[It] is woven, aware of its music, its overlapping waves of scenic action, so clearly on its way … like a magnet collecting details in its wake, each of which is essential to the final effect.”

At the same time, Toni was involved in Black and women’s liberation. She envisaged multicultural movements that crossed geographical boundaries, and in the early 1970s, she traveled to Cuba and Vietnam to learn from and forge connections with women’s organizations these countries.

Move to Atlanta

In 1974 Toni moved with her daughter to Atlanta, Georgia. Old family connections were part of her reason for moving: “My people are from Atlanta. My mama’s folks are from Atlanta. My Daddy’s folks are from Savannah. I’ve always been very at home in the South…”

There she taught writing and Afro-American Studies at Spelman College, Emory University and Atlanta University, and became involved in the Black Arts Movement as a writer-in-residence at the Neighborhood Arts Center. When Spelman turned down her proposal for a course specifically on Black women writers, she began to teach it from her home. This gathering became the Pamoja Writing Workshop, which later turned out award-winning writers such as Shay Youngblood and Nikky Finney.

Fellow Atlanta writer Pearl Clearge recalled that Toni said “that she didn’t like to call herself an artist because then it made you start acting precious like you were so above everybody else, that she thought we should call ourselves cultural workers because we were no better than people who worked in factories, no better than people who taught school, no better than people who were nurses and doctors and all of that. We were cultural workers.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

“A tremendous capacity for rage”— writing as activism

Between 1979 and 1981, a spate of about forty child kidnappings and murders — teens and young adults, mostly boys — rocked the Black community in Atlanta. Toni got involved in helping to disseminate accurate information, organizing neighborhood patrols, and monitoring the media amidst a climate of fear and mistrust.

Out of this came what many consider to be her finest novel, Those Bones Are Not My Child, originally titled If Blessings Come and published posthumously in 1999 by Toni Morrison. It was a testament to the power of Toni Cade Bambara’s passion for activism that had become the hallmark of her work.

In a 1982 interview with Kay Boneti of the American Audio Prose Library, Toni said, “When I look back at my work with any little distance the two characteristics that jump out at me is one, the tremendous capacity for laughter, but also a tremendous capacity for rage.”

In 1985 she relocated to Philadelphia, and taught film script writing at the Scribe Video Center. Alongside Louis Massiah, the founder of the Center, she worked on various documentaries. She sometimes produced, wrote, or narrated, and sometimes all three — including The Bombing of Osage Avenue (1985), and Seven Songs for Malcolm X (1993).

Toni was diagnosed with colon cancer in 1993. She continued to work, and one of her final projects was the 1995 documentary W.E.B. DuBois: A Documentary in Four Voices.

The Legacy of Toni Cade Bambara

Upon her death in 1995, the New York Times called her a “major contributor to the emerging genre of contemporary black women’s literature.” She was posthumously inducted into the Georgia Writers’ Hall of Fame in 2013, and since 2000, Spelman College has hosted an an annual Toni Cade Bambara Scholar-Activism Conference to honor her legacy of involvement in activism.

In 2025, the film TCB – The Toni Cade Bambara School of Organizing was released to critical acclaim, and won two documentary prizes at the BlackStar Film Festival. Directed by Louis Massiah and Monica Henriquez, it’s an intimate account of her life, told through archival footage, sound recordings, photos, animation, and interviews with her family, friends, students, and fellow writers and editors.

Further reading and sources

- Georgia Writers Hall of Fame

- Resembling a Revolutionary: My Sister Toni

- Remembering and Honoring Toni

- Bambara Archive at Spelman College

- Southern Collective of African American Writers

Major works

Short story collections

- Gorilla, My Love (1972; notable story: “Blues Ain’t No Mockin Bird”)

- The Lesson (1972; notable story: “The Lesson”)

- The Sea Birds Are Still Alive (1977; notable story: “Sweet Town” )

Novels

- The Salt Eaters (1980)

- Those Bones Are Not My Child (1999)

Screenplays (produced)

- Zora. WGBH-TV Boston, 1971

- The Johnson Girls. National Educational Television, 1972.

- Transactions. School of Social Work, Atlanta University 1979.

- The Long Night. American Broadcasting Co., 1981.

- Epitaph for Willie. K. Heran Productions, Inc., 1982.

- Tar Baby. Screenplay based on Toni Morrison’s novel, 1984.

- Raymond’s Run. Public Broadcasting System, 1985.

- The Bombing of Osage Avenue. WHYY-TV Philadelphia, 1986.

- Cecil B. Moore: Master Tactician of Direct Action. WHY-TV Philadelphia, 1987.

- W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography in Four Voices, 1995

Anthologies and biography

- The Black Woman: An Anthology (edited), 2005

- Deep Sightings and Rescue Missions: Fiction, Essays and Conversations

(edited by Toni Morrison), 1996 - A Joyous Revolt: Toni Cade Bambara, Writer and Activist

by Linda Janet Holmes, 2014

Leave a Reply