The Grimké Sisters’ Fight for Abolition and Women’s Rights

By Angelica Shirley Carpenter | On August 28, 2025 | Updated August 29, 2025 | Comments (0)

In 1838, Sarah and Angelina Grimké were likely the best-known — and most hated — women in the United States. Both published extensively, including essays and pamphlets promoting abolition and women’s rights.

Arm in Arm: The Grimké Sisters’ Fight for Abolition and Women’s Rights by Angelica Shirley Carpenter (Zest Books, 2025), introduces these fascinating figures to middle grade through high school readers, but can be enjoyed by all ages.

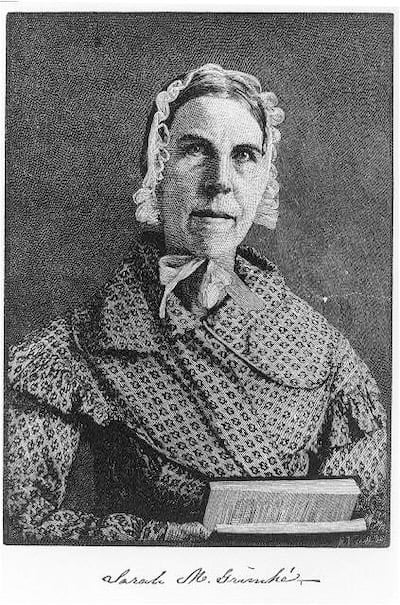

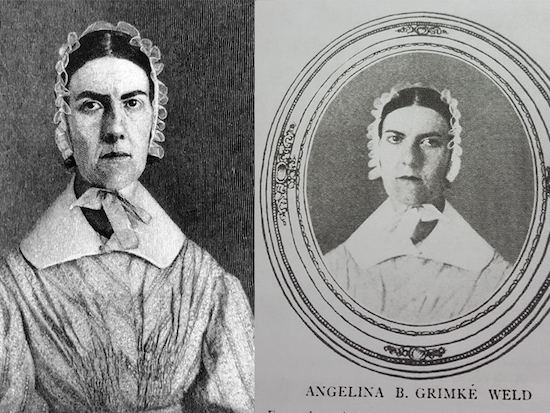

Sarah Grimké (1792 – 1873), the more reserved sister, preferred writing, while Angelina Grimké (1805 – 1879) loved the spotlight. Her spirited speeches often left audiences in tears.

Born to a wealthy family of enslavers in Charleston, South Carolina, they grew up in luxury, funded by the unpaid labor of three hundred men, women, and children. Of eleven Grimké children, only Sarah and Angelina turned against slavery.

Becoming abolitionists

As young adults, the sisters moved to Philadelphia and became Quakers. Then they became abolitionists, and were among the first women ever to speak in public in the United States. Women were not supposed to speak in public then, but the sisters did; at first to women only. Eventually men wanted to hear them, too, and they began to speak to mixed groups, a practice deemed sinful by many.

Newspapers called them “two fanatical women,” “old maids who wanted to attack society,” “abnormal creatures,” and “crack pots, cranks, and freaks.” So they added a second cause to their campaign: women’s rights. “We abolition women are turning the world upside down,” Angelina said.

The Congregational Church published a warning against them: “When woman assumes the place and tone of a man as a public reformer,” it said, “her character becomes unnatural . . . . the way [is] opened for degeneracy and ruin.” This criticism was based on the belief that women were inferior to men because Eve, by tempting Adam, had introduced evil into the world.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Sarah answers her critics

Sarah’s rebuttal, Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, and the Condition of Women (1838) is now considered the first complete feminist statement, foundational to the women’s movement. Sarah thought that God had created Adam and Eve as equals, who had committed the same sin of eating the forbidden fruit.

“Even admitting that Eve is the greater sinner,” she wrote, “it seems to me man might be satisfied with the dominion he has claimed and exercised for nearly six thousand years . . . All history attests that man has subjected women to his will, used her as a means to promote his selfish gratification, to minister to his sensual pleasures, to be instrumental in promoting his comfort; but never has he desired to elevate her to that rank she was created to fill.”

This book includes Sarah’s most famous quote, used often by the late supreme court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg: “I ask no favors for my sex,” Sarah wrote. “… All I ask of our brethren is, that they will take their feet from off our necks, and permit us to stand upright on that ground which God designed us to occupy.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

An important document

In 1838, Angelina became the first woman ever to address an American legislative body, at the Massachusetts State House. Later that year she married the famous abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld.

Two days after their wedding, she spoke about abolition and women’s rights at the new Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia. The next night, a pro-slavery mob burned it down.

Angelina and Theodore invited Sarah to live with them. The three retired from speaking, but kept writing. Together they produced the landmark American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses (1839), regarded as one of the “twin bibles” of the abolition movement, the other being Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) by the sisters’ friend Harriet Beecher Stowe.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

An expanded family of civil rights activists

Much later, when they had grown old, their lives took a surprising turn that enabled them to live out the principles they had believed in for decades. After the Civil War they learned that their brother Henry fathered three sons with his enslaved mistress.

The older boys, Archibald and Francis, attended college in Pennsylvania. The youngest attended briefly but went back south and lost contact. The sisters welcomed Archibald and Francis into their family. They went on to become leaders in the twentieth century civil rights movement. Archibald’s daughter, Angelina Weld Grimké, became a poet and playwright, a prominent figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

Who could fail to be inspired by Angelina Grimké Weld’s life motto: “I recognize no rights but human rights.”

About Arm in Arm and its author,

Angelica Shirley Carpenter

Historian Angelica Shirley Carpenter quotes primary sources to tell the sisters’ story in her new book, Arm in Arm: The Grimké Sisters’ Fight for Abolition and Women’s Rights (Zest Books, September 9, 2025). Published as a young adult biography, with many archival images, it has crossover appeal for adults, too, as Carpenter investigates why the sisters, once so famous, were later forgotten by historians.

Kirkus says “This relatively short book (296 pages) thoughtfully presents a period of upheaval and change and traces the sisters’ long-lasting impact as well as recent, more critical perceptions of their motivations and behavior that bring welcome nuance to their story.” School Library Journal deems the book “informative and engaging . . . . Recommended for all libraries.”

Back matter includes an author’s note, a Grimké family tree, a glossary, 26 pages of source notes, a selected bibliography, and suggestions for further reading.

In an earlier biography, Born Criminal: Matilda Joslyn Gage, Radical Suffragist (South Dakota Historical Society Press, 2018), Carpenter reintroduced a feminist leader who had been written out of history by her “friends,” Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Anthony and Stanton, but not Gage, play roles in Arm in Arm, too. Matilda Joslyn Gage, well aware of the Grimké sisters’ achievements, cited them as role models for her own, later work.

Angelica Shirley Carpenter’s complete bibliography and full reviews of the book may be seen on her website, angelicacarpenter.com.

Leave a Reply