Colonial America’s Intrepid Women Newspaper Publishers

By Taylor Jasmine | On June 10, 2024 | Updated November 10, 2025 | Comments (0)

It may be surprising to learn that a small but determined coterie of women published newspapers in the American colonies, before the states declared independence from Britain.

By the start of the American Revolution (1765), there were more than a dozen women printer-publishers operating on their own in the colonies. Most of them, called “widow-printers,” inherited their presses and newspapers after their husbands’ deaths.

Even so, it was rare for any woman to run a newspaper on her own. Not until much later could American women own property. They were property, though not to the extreme degree as their slaves and servants.

Women of all classes and races had no voice, no vote, no say in matters large or small. Running a newspaper was a rare feat of personal power for a woman in pre-Revolutionary times.

The early pioneers of journalism blazed trails for generations of women who came after them. From that time forward, journalists shared a sense of curiosity and empathy for others. They asked questions, made startling discoveries, and didn’t shy away from controversy.

Female journalists wore their independence proudly, often refusing to conform to gender roles and society’s limitations for women. The journalists you’ll meet ahead used the power of the press to advance women’s rights and civil rights, advocate for the end to slavery, report on war, improve labor conditions, and share accounts of triumph and accomplishment.

Most of all, they used their love for truth to tell a good story while striving to make the world a better, more just place.

. . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Glover

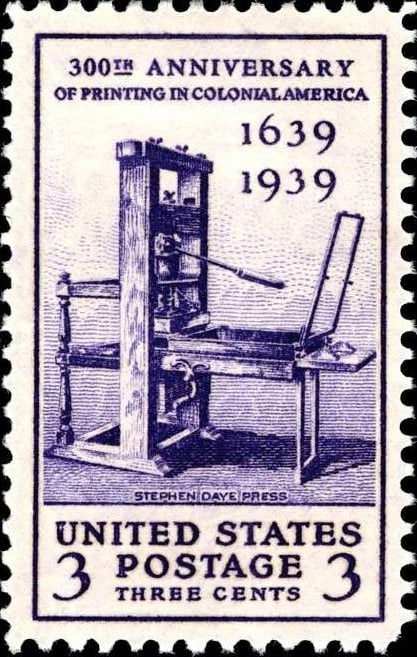

The earliest “first” of all happened long before the American Revolution. The first printing press came to the colonies in 1638 with the family of Reverend Joseph Glover of Surrey, England.

On board with him were his wife, Elizabeth Glover, and five children along with their furniture, linens, silver, a slew of indentured servants — and even some horses and cattle! They also brought their precious printing press, lots of paper, type cases, ink, and printers’ tools.

Reverend Glover died during the ocean voyage, but Mrs. Glover had the sense to install the press in the house she bought in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She started a printing enterprise that was later taken over by her second husband, the president of Harvard College (now Harvard University). Though they didn’t remain in the news business, we’ve got to give a nod to Mrs. Glover for getting the presses rolling.

. . . . . . . . . .

Elizabeth Ann Villin Timothy

Elizabeth Ann Villin Timothy

Printing was a difficult trade for anyone involved. Fathers passed along skills to their sons, yet many wives and daughters were also trained in the family business. Female colonists from printing families were luckier than most girls and women, many of whom were barely taught to read and write.

A woman who inherited a press had to be an excellent reader, writer, editor, and typesetter. And it didn’t hurt to have a head for business.

The widow-printers not only continued to run the newspapers left to them but made them grow and thrive. One of them was Elizabeth Ann Villin Timothy (1702 – 1757). Considered the first woman newspaper publisher in the colonies, she edited and printed the South Carolina Gazette in Charleston for seven years following her husband’s death.

When Elizabeth took over the paper, she published a notice in its pages asking readers “to continue their Favours and good Offices to this poor afflicted widow and six small children and another hourly expected.” Modern translation: “I have six kids and counting — please continue to subscribe to my newspaper!”

Elizabeth was fond of publishing dramas, poetry, and stories, especially by up-and-coming Southern writers. Not wishing to offend anyone, she mostly steered clear of politics and opinion. Thanks to her efforts, the paper was quite profitable. When she died, she passed the thriving Gazette on to one of her sons.

Elizabeth Timothy’s story is fairly typical of the early American widow-printers. Little else is known about her, and the same is true for most women of that era who took over their husbands’ newspaper businesses. Snippets and images of their newspapers survive, but portraits of the women themselves are quite rare.

As the post-revolutionary 1800s dawned, women involved with the news in any way clamored to voice their views on social and political issues, wishing to use their pens and presses to promote change.

. . . . . . . . . .

Anne Newport Royall

“Free thought, free speech, and a free press!” That was the rallying cry of Anne Newport Royall (1769 – 1854) considered America’s first female journalist. Growing up impoverished and fatherless, she started her youth and adult life as a domestic servant.

Her writing career was launched later in life with a series of books filled with colorful accounts of southern states and territories. That made her a pioneering travel journalist, and she also broke ground as a political and investigative reporter.

Always poor and forever struggling, Anne used all of her resources to start a newspaper. She was in her early 60s when she launched it in 1831 under the odd name Paul Pry. Later, she updated the name to The Huntress. There are no existing images of Anne Newport Royall, so we have to be content with an advertisement for Paul Pry, above.

In her own words, the paper was “dedicated to exposing all and every species of political evil and religious fraud, without fear or affection.”

Indeed, publishing her paper was hard going. It was written of her venture that “snow sometimes covered the floor where her paper was printed and the ink froze before it could record her blistering phrases.”

Anne was feared and scorned by Washington, D.C.’s powerful men — politicians, businessmen, and religious leaders — who dreaded seeing their names in her newspaper. But she dared to publish the truth. She was even convicted of being “a public scold” — which was actually a crime at the time!

Pushed down flights of stairs, beaten about the head, and ducking rocks thrown through her windows, nothing stopped her and no one intimidated her. She continued to publish The Huntress until she drew her last breath at age eighty-five, in 1854. It was all the more remarkable that she accomplished much of what she did before women officially began agitating for rights in the 19th century.

. . . . . . . . . .

See also:

4 Fearless American Female Newspaper Publishers of the 1800s

Leave a Reply